Minnie Reinhardt (1898-1986)

"First I check my board off in about four blocks each way -- that way you can put things more even in the right places. Then mostly I sketch off a house, maybe sometimes a barn. I just paint it on with a brush. Then the sky. [For the ground] I use burnt or raw umber, then I put your light on there like sun hitting places. Go back over it several times. About all of them has a house. I think they look more alive. I like to put people and live things, dogs, in it. I like dogs and live things."

The memory paintings of Minnie Smith Reinhardt illustrate life in the rural North Carolina farming community where she grew up. Known then as Jugtown for all the clay pottery made there (including by Reinhardt's father), the area is now called Vale. She was one of eleven children who all had to help out on the family farm from an early age. School was a respite from all that hard work for a few months each year. There, Reinhardt could sometimes just sit and draw, first with chalk on slate and later with the luxury of colorful crayons.

When Reinhardt was "about eighteen" in her recollection, she started work at Lenoir-Rhyne College as a cook. "That's where I learned to sew and not use a pattern. Then I sewed for the public after I was married [to Belton Reinhardt]. ... They'd bring me a picture of what they wanted, and I'd cut out a pattern and make it. I sewed for the whole county - they'd come from Lincolnton and Hickory." (From Barry G. Huffman's unpublished manuscript Different Visions.) Reinhardt also, of course, was cooking, washing, ironing, raising the six children, and helping in the fields. While she had no time to paint then, all these activities over the years from childhood on eventually became the subjects for her paintings.

Above: On The Farm. 1977. Oil on canvas board. On right: Bringing Home the Christmas Tree.1984. Oil on canvas board.

By 1974, cataracts had diminished Reinhardt's vision to the point that she had difficulty distinguishing shapes and colors. She underwent surgery, and the experience of suddenly seeing colors and details clearly again motivated her to begin painting in earnest, using oil paints given to her by her daughter Arie Taylor (also a painter). Reinhardt taught herself some techniques from books but “Mine’s my style” as she said when Taylor tried to instruct her.

Reinhardt's paintings are filled with people and animals in the midst of daily activities specific to each calendar season as she remembered these scenes, but she didn't romanticize that life in her paintings. Although the seeming simplicity of her paintings may inspire nostalgia for a seemingly simpler time, she showed all the hard work it took to provide for yourself and your family on a small farm.

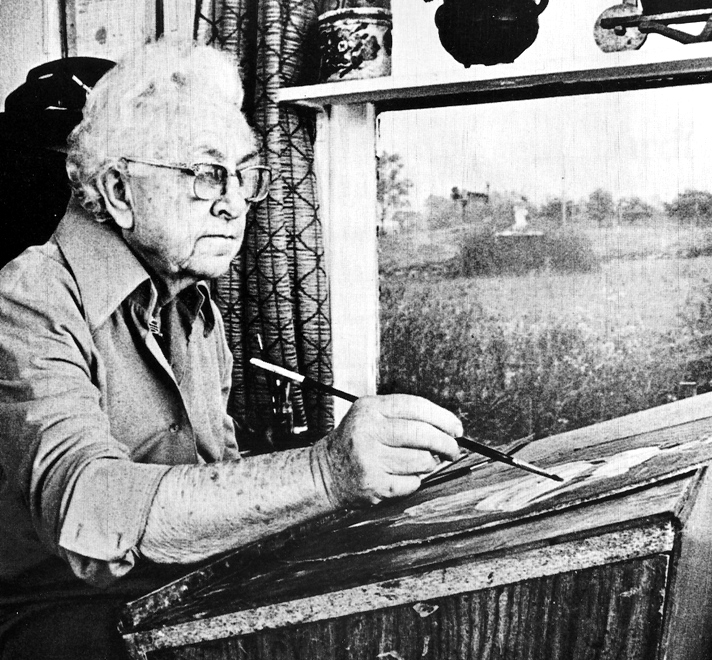

Reinhardt was extremely prolific from then until her death twelve years later, painting daily at home at a small desk in front of a window. In a 1984 interview she observed that, "There's not anybody now, I don't think, who paints that saw what I saw, like cutting wheat and picking cotton and making molasses and all that stuff. ... I went through all that. If you didn't you wouldn't know how to paint it." Her husband made many of the frames for her finished paintings.

In 1996, HMA hosted an exhibit of almost 100 of Reinhardt's works, many on loan from individual collectors and small organizations along with works already owned by HMA. This slanted desk in the exhibit is the actual desk at which Reinhardt painted.

A selection of Reinhardt's works were featured in the Museum's s Folk Art Exhibit through 2022. . One of her works was part of the exhibit Woman Made that showcased works by women artists in the Museum's permanent collection. That show opened December 17, 2016 and ran through April 23, 2017.

This post is # 22 of the 75 stories to celebrate HMA's 75 years.

Post by Karin Borei, HMA Project Coordinator, writer and editor as needed, and HMA blogger since our blog's inception in March 2015